From the vantage point of space, NASA’s fleet of Earth-observing satellites joins with those of partner interagency and international agencies to investigate and illuminate connections between ecosystems that are continents apart, or right next door. With a global perspective, scientists can observe how factors like deforestation, climate change and disasters impact forests and other plant life – while also studying how changes in vegetation impact air quality, waterways and the climate. Vegetation is the primary energy source for nearly all life on Earth, so monitoring it and forecasting how it could be impacted by climate change is key.

In the Amazon, NASA Earth scientists monitor forests and bring these data into the hands of local decision-makers. NASA data provides information about the clearing of trees for agriculture and ranching as well as the impacts of drought on tree mortality. People cut down forests and then ignite the piles of trees and other vegetation, leading to wildfires, which can be detected by instruments including the thermal imager on the Suomi NPP satellite. In 2020, these sensors detected where 1.4 million fires took place. The fires generate smoke that can drift over the continent and be seen from space.

With instruments that collect images of Earth’s surface, researchers can also track the scale of those fires and forest clearings over the years, and even over decades. With the joint NASA/U.S. Geological Survey’s Landsat mission, which launched its first satellite in 1972 and is scheduled to launch Landsat 9 in September 2021, scientists can track changing patterns of deforestation that tells them how Amazonian agricultural practices have changed, from small family holdings to massive ranching operations.

Tracking Plant Health from Space

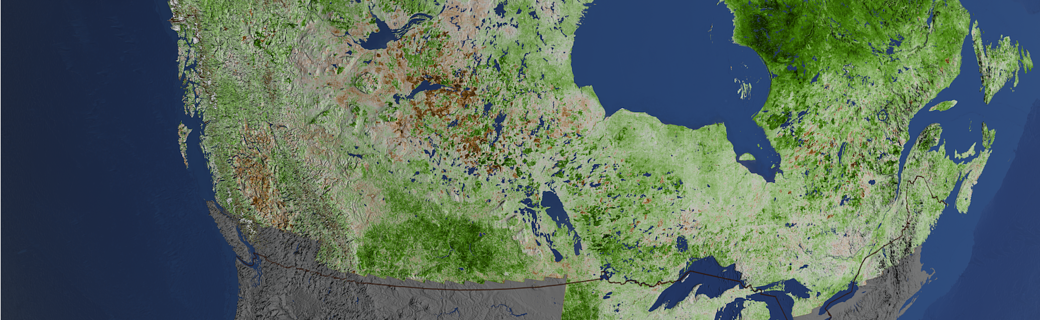

Satellites can detect how “green” an area is – showing the health of plants that are growing in a particular site. While fires, deforestation and drought lead to the tropical Amazon being less green, warming temperatures in the Arctic lead to tundra and boreal regions becoming greener. Using 87,000 Landsat images spanning nearly three decades, scientists found that a third of the land cover of Canada and Alaska looked different in 2012 as compared to 1985. With warmer temperatures, and longer growing seasons, shrubs become denser on grassy tundras, transforming what they looked like from space.

Since plants take up carbon dioxide from the air as they undergo photosynthesis to make food, it may seem that having a greener Arctic would a result in less of the greenhouse gas in the atmosphere. However, a recent study using satellite data and computer models found that any increased carbon uptake in the Arctic is offset by a decline in the tropics. There, warmer global temperatures have led to a drier atmosphere. That means less rainfall and more drought in places like the Amazon, which leads to a drop in tree growth and increases in tree mortality – and less carbon taken from the atmosphere. Soon, water availability could limit the amount of greening in the Arctic as well, the scientists found. As forests expand or are cut back, researchers use data from instruments including MODIS and satellites like Landsat to measure their extent and health.

A new suite of NASA instruments in space also measure the health of forests. The Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation – or GEDI – instrument aboard the International Space Station uses lasers to measure the height of trees, allowing researchers to investigate how ecosystems are changing and how the carbon and water cycles are shifting in a warming climate. The Ice, Cloud and land Elevation Satellite 2, or ICESat-2, uses a similar technique to measure heights, and can reach higher latitudes to see changes in the Arctic biomes as well. And the Ecosystem Spaceborne Thermal Radiometer Experiment on Space Station, or ECOSTRESS, measures the temperature of plants, to help determine their water consumption and health.

From Forests to Farms

While climate change impacts the growth and health of vegetation, naturally occurring weather patterns have an impact as well. Scientists with NASA Harvest are looking into the connections between El Niño/La Niña weather patterns, and the farming conditions and crop yields in eastern and southern Africa. During El Niño years, winds and currents in the equatorial Pacific Ocean cause water to pile up against South America, impacting weather patterns around the globe – even in Africa. Researchers found that southern Africa tends to have decreased crop yields during El Niño phases, while eastern Africa sees increased crop yields in those years – knowing these relationships can help farmers and policy makers prepare for a given season.

NASA satellites and science also help farmers in the United States monitor and track their crops. Having more information about rainfall, plant health and other data gives farmers information they use to deal with the extreme weather events that are increasing due to climate change, as well as shifting planting zones and other effects like early freezes and heavier spring rains. The U.S. Department of Agriculture estimates and tracks crop production using farmer surveys and ground observations, with a big-picture assist from Landsat data, NASA computer models and other Earth science resources. They also use MODIS instruments to monitor daily vegetation health – all to help determine what the crop yield will be, and which areas could be facing problems.

These same satellites can also help scientists track the unwanted products of some agricultural fields, including runoff that flows into waterways. Farms, forests, tundra – all these vegetated ecosystems connect to other spheres of our home planet.

By Kate Ramsayer

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

Reposted from original article

Comments are closed.